The three men in this article no longer exist in the consciousness of Japanese society. On 7th December it will be exactly 60 years since they took part in the attack on the US Navy’s Pacific fleet in Pearl Harbor on the Hawaiian island of Oahu.

The attack, by 350 aircraft from the carriers of the Japanese First Air Fleet and a number of midget submarines, left over 2,330 Americans dead and caused considerable damage to numerous ships including four American battleships that were either blown up or sunk. The raid also hit the airfields on the island with 188 US aircraft destroyed on the ground. Japan’s ten battleships were left as the dominant remaining naval force in the Pacific.

After the war, the three Japanese airmen, together with their surviving comrades from all branches of the Imperial Japanese military were either ignored or shunned by their fellow citizens. Desperate to put the humiliation of defeat and the horrors the war had brought to Japan behind them, the population chose to turn their backs on the men they had fanatically supported.

The attitude of indifference and deliberate lack of curiosity was epitomised by a Japanese parliamentary session in 1991, when the issue of the 50th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor was raised. An official from the Japanese foreign ministry simply stated that all those who had been involved were now dead, implying that the subject was not even worthy of discussion.

As we near the 60th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Takeshi Maeda, Zenji Abe and Kaname Harada remain amongst the few surviving Japanese witnesses to the opening act of aggression which triggered the war against America in the last century. The lives they have led since, stand as a testament to the power of reconciliation. With all of them involving themselves in meetings with their former enemies and other initiatives to promote peace and understanding, they are a reminder that – with courage – we are all capable of change.

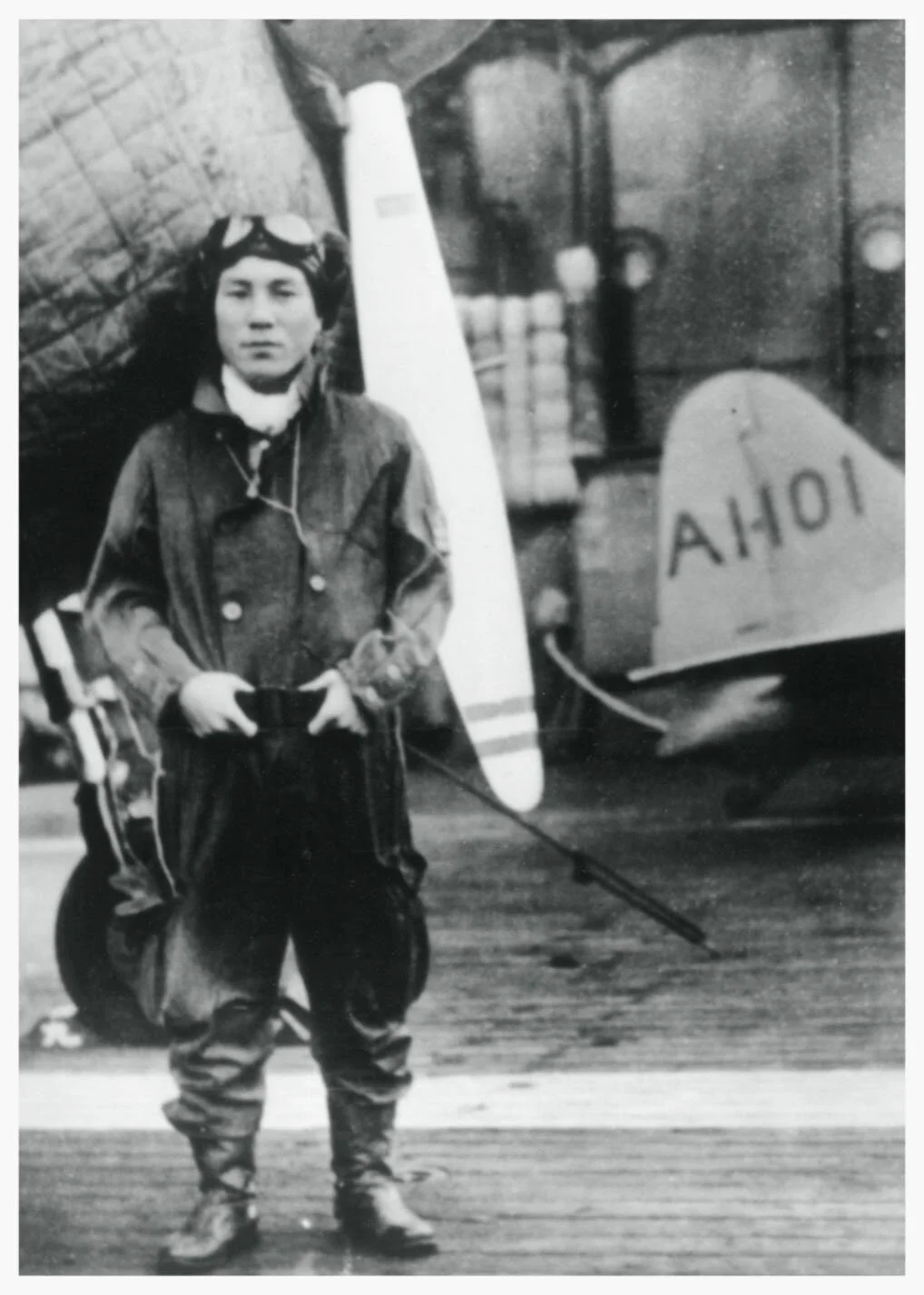

Takeshi Maeda

Torpedo bomber

Photos: Takeshi Maeda in 2001 and 1939.

Brought up by his disciplinarian father, Takeshi Maeda's childhood dream of becoming a painter was never to be realised. Instead, he was persuaded to follow a career more aligned to his country's ambitions and joined the Imperial Japanese Navy in 1938. Three years later, when Maeda was just 20 years old, he was to play a role in one of the defining historical events of the 20th century. As the navigator on board a Japanese Navy torpedo bomber, he took part in a surprise attack on the world's most powerful nation. The raid on Pearl Harbor lead to a savagely fought war between the two countries, culminating in the destruction of two Japanese cities by the first atomic bombs to be used in warfare.

As the first wave of 183 Japanese planes left their aircraft carriers and headed towards war, Maeda's radio picked up Glen Miller's Sunrise Serenade being broadcast to the US forces in Hawaii. He felt reassured that the Americans could not possibly be expecting the imminent attack on Pearl Harbor. Contrary to popular belief, 'Tora, Tora, Tora' was not a verbal command to start the surprise attack. It was the Morse Code signal sent back to Admiral Yamamoto to inform him that no US aircraft had been sighted, allowing the Japanese to continue with their strategy. With radio silence strictly enforced, the command to attack was never voiced, but signalled by a flare fired by Mitsuo Fuchida, the attack commander, from his aircraft.

On seeing Fuchida's flare, Maeda remembers all forty torpedo bombers forming a single file for the final approach. Each crew was assigned a specific target; his was the USS West Virginia. Despite being only the second aircraft in, he was surprised at the speed of the American reaction, his plane jolting violently as it was hit by anti aircraft fire. The remaining crews were not so fortunate, the last five bombers were shot down. After Maeda’s direct hit on the West Virginia, a further eight torpedoes struck the vessel, sinking her to the bottom of the harbour. With the first wave of the attack completed in just half an hour, Maeda's part had taken little more than a minute. However, far from being relieved, Maeda recalls his greatest worry was finding his way back to his carrier, the Kaga, some 300 miles away over a featureless sea.

Maeda’s bomber carried a single 830Kg air torpedo that had been modified for use in shallow water. Special fins prevented the torpedo from diving too deeply beneath the surface and getting stuck in the mud. ‘We underwent six months of intensive training in preparation for the attack, although at the time we did not know that Pearl Harbor was to be our target. To enable us to launch the torpedoes in the short tracts of water we reduced our approach from the minimum 1000 metres to just 700 metres. Because we had to clear the harbour buildings before dropping to 10 metres above the water, it was critical that we got the approach just right.’ The short run up meant that the torpedo bombers were in danger of clipping the tops of the ships they were attacking.

One consequence of the shallow water at Pearl Harbor was to return and taunt Maeda later on in the war. At the battle of Okinawa in 1945, he was taking part in a night attack against a group of US ships. ‘Flares were dropped from spotter aircraft to illuminate the ships as we moved in. Suddenly, there before me was the West Virginia, the very ship I had torpedoed and sunk in Pearl Harbor. I couldn’t believe it.’ The resourceful Americans had managed to salvage and repair many of the ships that had been sunk or damaged. The shallow water and confined conditions of the port that had so tested the ingenuity and courage of the Japanese torpedo bombers made the Americans’ subsequent task of recovering the ships that much easier. In the end, only three vessels were permanently lost.

Maeda is now an alert and apparently serene 80 year old, who has spent most of his civilian life working quietly for a big Japanese corporation. His views on warfare have now changed. He has taken part in numerous reconciliation initiatives, and in 1991 he made headlines across America with a speech he made in English at a 50th Anniversary Symposium for the US Pearl Harbor Association in Hawaii, which ended with the words "Pearl Harbor - never again." The many close American friends he has made since include several who where on the West Virginia when he sank it.

Although he flew in every major action of the Pacific war, Maeda’s only injury occurred when he was shot through the leg at the battle of Midway. Finally, in August 1945, he was forced to join the ranks of the Kamikaze pilots’ Special Attack Force. ‘I had accumulated 3,800 hours of combat flying experience. I couldn’t believe my commanders wanted to waste all that in a single mission.’ It was at this point that he first realised the fallibility of his leaders and the recklessness with which they had treated the lives of the Japanese people. It is an opinion he has held ever since. He feels the Americans’ decision to use atomic weapons against Japan was in revenge for the attack on Pearl Harbor. However, he believes that ultimately it resulted in the saving of more Japanese lives than were lost; the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki led Emperor Hirohito to urge his people to surrender on 14th August, just two days before Maeda was due to make his Kamikaze flight.

Takeshi Maeda died aged 98 on 29th July, 2019. He was the last surviving airman directly involved in the attack on Pearl Harbor.

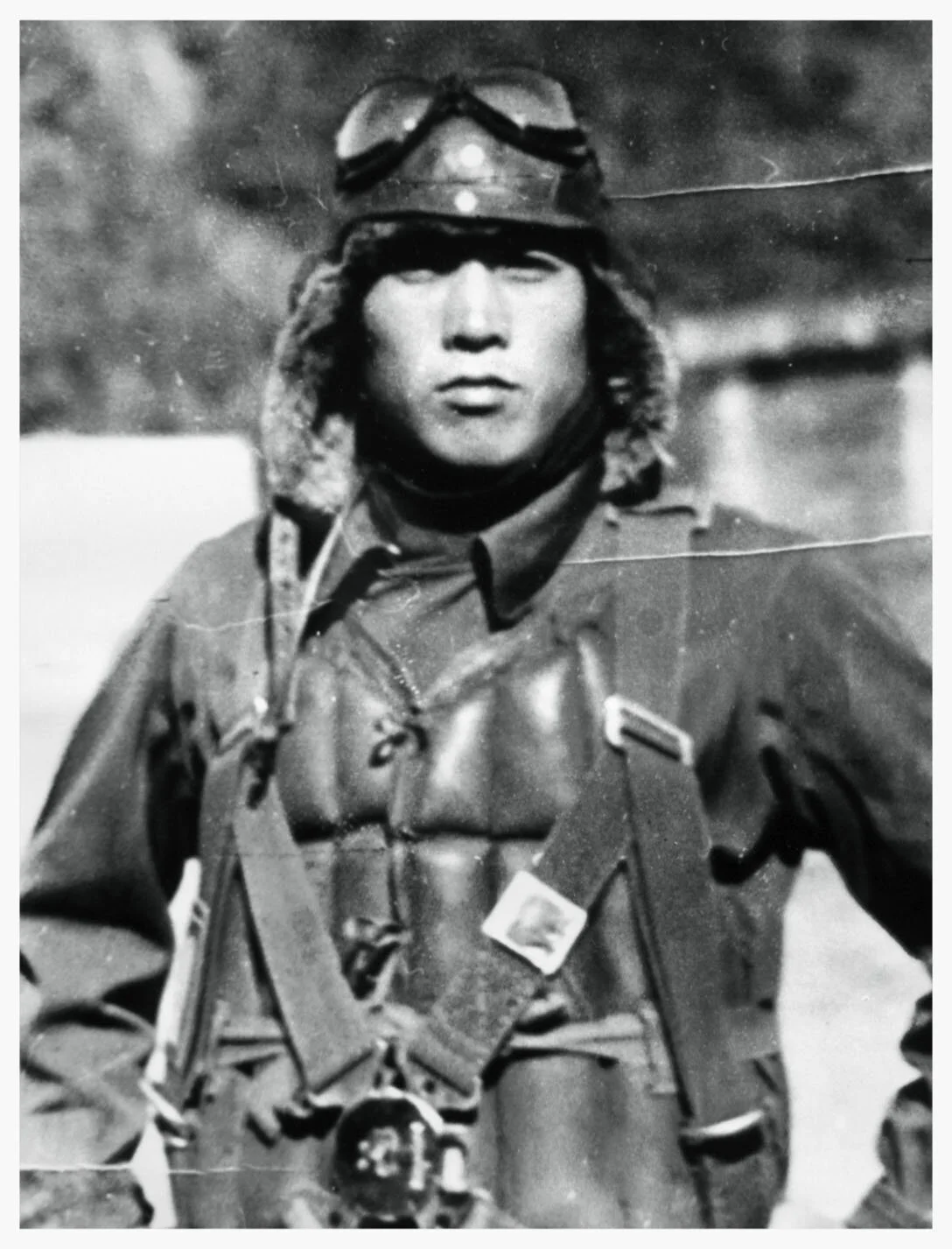

Zenji Abe

Dive bomber

Photos: Zenji Abe in 2001 and on the aircraft carrier Akagi in 1941.

When Lieutenant Abe’s dive-bomber tipped into its steep attack over the Battleship Arizona the ship was already ablaze, its forward magazines having been detonated in a colossal explosion caused by an earlier bomb dropped in the first wave. His single 250kg bomb, released at 400 metres, contributed further to the destruction below. 1,177 US servicemen were killed on the Arizona.

This brief attack by the dive-bomber was the culmination of some of the most rigorous military training undertaken by airmen anywhere in the world. Zenji Abe, now approaching his 85th birthday, recalls just how brutal his training in the Imperial Japanese Navy was; ‘From the moment the early morning wake-up call was given, we had exactly two minutes to get dressed, make our beds extremely neatly and get to the wash house 150 metres away. Anyone who was untidy or so much as a second late was taken away and severely beaten.’ An important feature of his four years of training at the naval academy was that absolutely every minute of his time was carefully scheduled and controlled; ‘We never had a single moment to relax or spend doing what we chose.’ The absolute discipline and blind focus on obeying orders without question forged Abe and his comrades into lethal agents of the Japanese regime. ‘The Japanese were brainwashed into believing that their country was a divine nation, blessed by having a god as its leader – the Emperor.’

In their preparations for the attack on Pearl Harbor, the military pushed its men and their machines to absolute limits. The dive-bombers were designed to release their bombs at 800 metres, allowing sufficient time to come out of the dive. To increase effectiveness the commanders ordered this to be reduced by half. Dropping their bombs at 400 metres meant that aircraft cleared the ground by just 15 metres as they came out of the dive. Abe recalls, ‘Unless your eyes stopped seeing for a few seconds because of the G-force involved in pulling out of such a low altitude dive, you knew you weren’t going to make it’. At least eight airmen where killed during training. The effect on bombing accuracy was spectacular – improving from 20% to 86%.

On the day of the attack, Abe got up at 3:00am local time on his carrier the Akagi. For such an important mission he and his colleagues would all wear their best uniforms under their flying suits. After writing a letter to his wife and placing it in his locker, he visited a small shrine on the ship to pray. He then joined his fellow airmen for breakfast and the final briefing. They could hear the noise of the planes’ engines being warmed up on the flight deck resounding through the whole ship.

It took just fifteen minutes for all 167 second wave aircraft from the six carriers to get into flight formation. This was a considerable feat and a testament to the skills of all involved, especially as all radio contact between aircraft and with the ships was strictly forbidden. Given the enforced radio silence, the planes flew in extremely tight formation to enable visual contact between the airmen by means of hand signals and facial gestures. Within each squadron of nine aircraft, a distance of just one metre was maintained between each plane as they flew onwards at staggered altitudes to avoid propeller turbulence. ‘As my Squadron flew at the highest point and at the back of the formation, I had a good view of all the aircraft flying ahead of me. I felt very proud, like a shepherd guiding his sheep.’

His recollections of the attack itself centre on how well the Americans had recovered from the surprise of the first wave just thirty minutes earlier. As squadron leader, he watched two of his planes being shot down before making his own successful dive on the Arizona. The three bombers that followed him were all downed by heavy enemy fire. Back at the rendezvous point, with a number of his colleagues already dead and the shock of seeing how badly some of his planes had been damaged, the stark reality of war hit Abe, casting its shadow over yet another young mind.

He took part in a further five missions after Pearl Harbor, the last of which was a No Return Mission attacking US Task Force 58. This meant an attack beyond the effective return range of his aircraft back to the carrier - he would have to attempt a landing elsewhere near the site of the attack. After locating the American fleet (3 aircraft carriers surrounded by 20 other US vessels in a protective ring formation) he ordered his squadron to attack and launched his own aircraft into a dive through a hail of anti-aircraft fire, after dropping his bomb he withdrew beyond range of the ships’ guns and waited for his comrades. It was at this point that several US fighters came towards him. He managed to evade them with the help of cloud cover, and with his fuel rapidly running out, finally managed to land on the tiny island of Rota, 32 miles northeast of Guam in the western Pacific. Of the 430 Japanese planes involved in the attack, all but thirty were shot down. He subsequently surrendered to the Americans on the 15th August 1945.

After the war, Abe lost all contact with his ex-comrades in the navy. Then in 1991, on the 50th anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, he attended the commemoration meeting of the US Pearl Harbor Association in Hawaii. His desire for atonement lead him to form the ‘Japanese Friends of Pearl Harbor’. He drew up a list of survivors, which numbered around 80 at that time, and visited each of them individually to explain what he was doing. Today, he estimates only five other people remain who are still able to talk about their experience. Since his first trip to the US in 1991, Abe has returned many times and has devoted himself tirelessly to acts of reconciliation, helping to ease some of the deep scars inflicted during those terrible moments of 60 years ago.

Zenji Abe died aged 92 on the 6th April 2007.

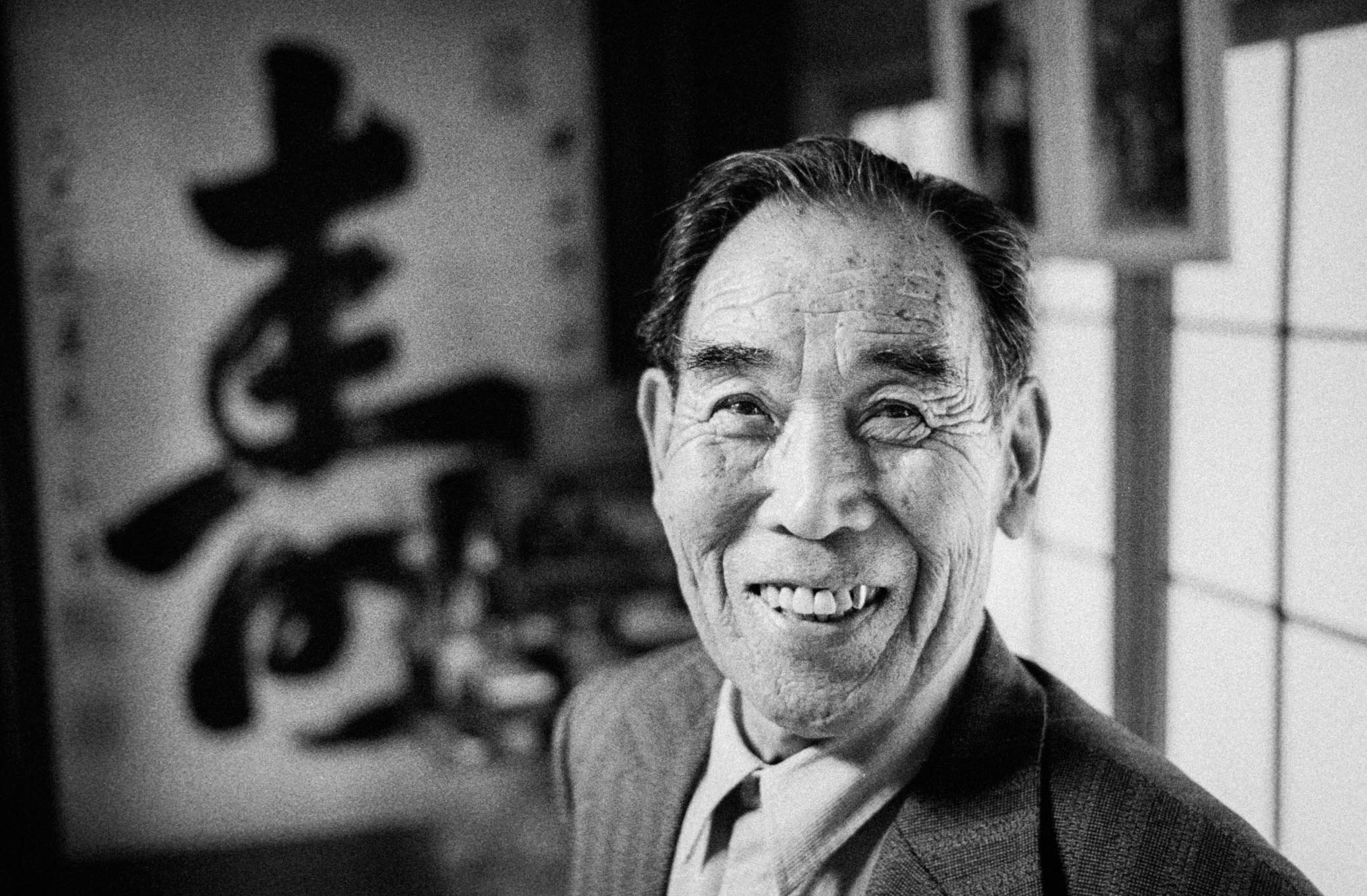

Kaname Harada

Zero fighter pilot

Photos: Kaname Harada in 2001 and1938.

Kaname Harada was a natural pilot. Of the 1500 men who signed up with him to become navy pilots, only 26 completed the brutal four year selection and training process. Harada was awarded a watch by the Emperor for being the best graduate in his cohort. Strong, handsome and intelligent, he was the perfect candidate for the Japanese military. Now 85 and still running his own kindergarten in Nagano, Harada has a very different outlook on life.

When Harada was assigned to the aircraft carrier Soryu in September 1941 and training was stepped up, he sent his pregnant wife, Sei, back to the family home in Nagano. In accordance with Japanese culture, neither of them had shown any emotion when they said goodbye – something Harada’s wife made up for by writing to him every day until his ship’s departure. ‘My colleagues used to joke that it was like the daily papers arriving,’ he says.

When the ship left, the external pipes had all been lagged for protection against cold weather convincing him they were on their way to attack the Soviet Union. In fact, his vessel followed a route via the Aleutian Islands to the north before its approach to Hawaii. This was done to help conceal their true plans from the Americans. It was not until 24th November Harada learnt that Pearl Harbor was to be their target.

His role at Pearl Harbor caused him bitter disappointment at the time. As one of Japan's elite fighter pilots, he spent the night before with his fellow Zero pilots toasting their expected success against the US. So when Harada was informed that he would not be attacking Pearl Harbor directly, but assigned to combat patrol protecting the bombers and the fleet, he begged his superiors to allow him to take part in the main attack. His request was refused, and consequently he flew an unchallenged patrol, whilst colleagues in his squadron – three of whom would not return – took part in the main raid, destroying planes on the ground. Whilst the returning airmen were jubilant that the attack had been a success, he remembers feeling the opposite when he discovered that the US aircraft carriers of the Pacific fleet had not been in port. Crucially for the subsequent stages of the war, they had escaped the Japanese attack.

Harada’s relatively low-key involvement at Pearl Harbor was not to last throughout the war. On 5th April 1942 in dogfights with the British over the island of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), he was credited with shooting down five Hurricanes in a single day (with three independently confirmed). The superior manoeuvrability of his Mitsubishi Zero, which allowed him to fight in so close, now only serves to haunt him as he remembers the stricken faces of the men he shot down. He clearly remembers one of the British pilots skilfully landing his shattered plane in a paddy field.

At the Battle of Midway, he shot down five US torpedo bombers (all confirmed) attacking the Japanese fleet, but others would get through. Four Japanese heavy carriers – including Harada’s – were destroyed by the Americans. This marked a decisive turning point in the war. With nowhere to land, Harada’s Zero eventually ran out of fuel. He still has the watch he was wearing, forever stuck at 3:26pm – the moment he ditched into the sea. Although he survived his first crash landing unscathed, his second was to prove a harsher experience. In a protracted dogfight with a US Wildcat Fighter over the South Pacific Island of Guadalcanal, Harada was shot down. The battle culminated in the American airman – Joe Foss – and Harada flying directly at each other with machine guns blazing. Shot through the arm and with his plane badly damaged, he crash landed in the jungle.

There he came across a Japanese bomber that had also been shot down: one crewman was dead with the other hopelessly injured. The injured man begged Harada to cut off some of his hair and take it back to his family and to leave him and save his own life. Harada, however, stayed with the man until he died – later learning that, in doing so, he had saved his own life. The delay stopped him crossing the path of the US forces in whose direction he was walking.

After the war, Harada along with most ex-servicemen was snubbed by the Japanese people. Forbidden from working in any kind of educational or political role, he was forced to take dead-end jobs for the next 25 years – "selling apples, milking cows and working as a farm labourer.... I tried everything I could but it all failed." In 1965 he and his wife started a small nursery to help local mothers. Four years later and finally with the support of the local community he started a kindergarten for the children of Nagano.

In 1991 on the 50th anniversary of Pearl Harbor, Harada travelled to the US in search of forgiveness. Like most of his generation, it was here that he first found out that Japan only declared war on the US after the attack on Pearl Harbor – something that had never been made public in Japan. He also met Joe Foss, the US pilot who shot him down. Drawn together by the ferocious duel they had fought in their youth, in which Foss's plane had been punctured 240 times, they became friends.

After his earlier life of blind obedience and military discipline, and with 19 confirmed air to air kills, Harada now understands the vital role of education in avoiding it all happening again. Over the last 30 years he has spent a lot of his time speaking at schools, both in Japan and the US. Teaching and helping new generations is Harada’s personal attempt at salvation.

As he nears the end of his life, his final wish is to meet the families of the Hurricane pilots he encountered all those years ago. He tentatively hopes the pilot who landed in the rice field will still be amongst them.

Kaname Harada died aged aged 99 on the 3rd May 2016. He worked at his beloved kindergarten until he was 95 and remained a tireless peace activist until his death. Kaname Harada was the last known surviving fighter pilot who flew the legendary Zero in combat.

From media project to reconciliation initiative

The Pearl Harbor feature started out as an ambitious project to find and interview surviving Japanese airmen who flew in the three primary types of aircraft used in the 1941 attack. From inception to completion the project ran over 18 months, requiring multiple visits to Japan. The aim was to offer a completed feature, with copy and portraits, to the Sunday broadsheets on a speculative basis.

In the beginning we were told that only a few men involved in the action would still be alive, and those that were would be unwilling or unable to speak to us. Whilst it was a real challenge to find the airmen matching our self-set brief, once contact had been established, it was just a question of following Japanese protocol to arrange the initial meetings. Any concerns we had about the airmen being unwilling to speak to us quickly evaporated during the introductory meetings. In each case the former airmen and their families could not have been more enthusiastic with their welcome and generous with their time.

In the lead-up to the 60th anniversary on the 7th December 2001, the Pearl Harbor feature was syndicated to publications in 14 countries, including Japan and the USA – first published by the UK’s Sunday Independent in March 2001.

Following publication, interest in the pilots' experiences led to a number of reconciliation initiatives, one of which led to the meeting between Kaname Harada and John Sykes, the British pilot Mr Harada had shot down over Ceylon. With the help of Christopher Shores, a military aviation historian, and Air Commodore Rick Peacock-Edwards (retired), who’s father had served alongside John Sykes, it was possible to establish beyond reasonable doubt that John Sykes had been shot down by Kaname Harada.

When the two pilots finally met, their week together – which included pub lunches, museum visits and celebratory dinners – attracted considerable interest from newspapers and TV networks, including the BBC and Sky News. A programme documenting Mr Harada's visit to the UK was aired on Japanese national TV in 2002.

Mr Harada’s final wish whilst in the UK was to visit the Runnymede Air Forces Memorial, dedicated to the 20,456 men and women from air forces of the British Empire who were lost in air and other operations during World War II. During his visit, Mr Harada broke down in tears and told us that his war was finally over.

Commander John Sykes with Kaname Harada.

With the help of Christopher Shores, a military aviation historian, it was possible to establish beyond reasonable doubt that John Sykes had been shot down by Kaname Harada.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our deep gratitude to the airmen and their families, for their warm welcome, their hospitality, and for giving us their time so generously to recall and share their memories. Special thanks also to Christopher Shores, the military aviation historian, and Air Commodore Rick Peacock-Edwards (retired) for their meticulous research into the air battles involving Commander John Sykes and Kaname Harada over Ceylon (now Sri Lanka).

Thank you to Minoru Yamada, Hiroshi Shinjo, Yasuto Kato, Hyper-Noguchi and Micky Grace for their assistance with this project.

Research and translation by Tomoko Nishizaki, Stephan Kassippilai and Marcus Perkins.